I’ve just finished reading The Human Zoo by Desmond Morris, which, in reprints, bears the subtitle, ‘A Zoologist’s Classic Study of the Urban Animal’. It reads and feels like a classic, and I was glad to find an old (1971) edition at the Lifeline Book Fair last year. The dustjacket is haggard, bearing a meagre black typeface on a red background, barely covering a cloth-bound hardback with yellowed pages I was originally reluctant to mark with a pen or even subject to dog-earing.

I was also not compelled to mark the text because, frankly, the insights and ideas in the book are not exactly thrilling or groundbreaking ~ I didn’t find that much to remark upon, at least in the early chapters. By the end, especially in the chapter, ‘The Childlike Adult’, I was feeling somewhat more moved.

The book does open with a compelling notion to challenge the criticism of modernity as a ‘concrete jungle’: Morris goes one further, saying it’s worse than a jungle ~ it’s a human zoo, where captive human animals murder each other, waste their energy on the pursuit of unnecessary status symbols, and masturbate furiously to kill time and get a dopamine hit, which are things that wild animals apparently do not do. One of my favourite t-shirts reads ‘concrete jungle’, so now I feel like a bit of a chump when I wear that.

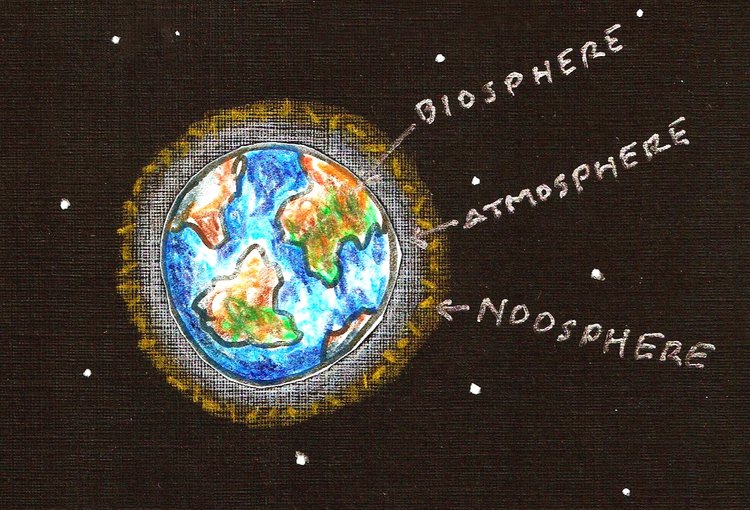

He also touches on something raised by Alvin Toffler in his book Future Shock, which is the basic idea that humans have not evolved biologically to keep up with the pace of evolution we see in technology and industry: we’re simply not designed to live in the sorts of environments that now surround us. He talks about this in terms of ‘tribes and super-tribes’, which is the title of his first chapter:

there was a time in our evolutionary history where every one of the 120-or-so members of the tribe/village knew everyone else, and there were very few stressors beyond the demands of hunting and gathering, maybe tending a few crops after we invented farming; now that we’re living in super-tribes, where anonymity is the default, we are beginning to suffer from problems like fixation with ‘super-status’ (chapter two), and addictions to ‘super-sex’ (chapter three).

(I say ‘beginning to’, but remember Morris’s observations were being made in the late 60s early 70s, so we’re 50-odd-years down the path he pointed out for us way back then.)m

It was a vaguely entertaining light-read, but many of Morris’s observations are limited by the catch-all ‘super’ qualifier, and many are super-reductive and over-simplistic. In Chapter 5, ‘Imprinting and Mal-imprinting’, he claims that homosexuality is an aberration resulting from problematic upbringing. In Chapter 6, ‘The Stimulus Struggle’, he reduces the history of human art to nothing more than a pursuit of stimulus ~ we are so under-stimulated because we don’t have to hunt or gather anymore, that we make art for the sake of trinkets. And he attributes all guitar-playing to a phallic fixation.

These ideas are patently ridiculous, and were difficult to read without vomiting scorn into my mouth. He has a tendency to make such claims, provide some evidence that could (at a stretch) be interpreted as support for that claim, completely ignore the possibility of other interpretations, and then say, ‘See, I proved that all guitarists are repressed wankers.’

He introduces a nice idea at the end: that if adults can retain their childlike qualities as they age, we can hope to find creative and explorative ways out of the situation we’ve created for ourselves. It was an interesting book to read, even if it was a bit glib and mostly bland ~ maybe these were profound insights 50 years ago, but I think anyone reading this with even a vague sense of awareness about the world today would not be surprised or freshly enlightened to read them. It’s a classic text that I was excited to find and read, and I’ll probably check out his Naked Ape if I find it in the two-dollar pile at next year’s book fair, but I don’t think I’ll deliberately hunt it down.

And despite my reflex to dismiss the whole thing as the rambling half-thoughts of a drunken uncle at Christmas, the book still falls into my category of paradigm-expanding texts: reading it has reminded me, again, that living in the modern world comes with consequences extending their roots all the way back to the dawn of humanity. After reading such a book, when I stress about uni or finances or getting another cold sore after three sleepless nights in a row, I don’t beat up on myself so much for having trouble coping. It’s a veritable zoo out there ~ the conditions we have created for ourselves are not exactly conducive to that wild sort of happiness we tend to expect from life. So if I’m happy some of the time, and not depressed most of the time, I think I’m doing alright.